Sketchnoting & the big box of crayons: Lesson for a journalism teacher

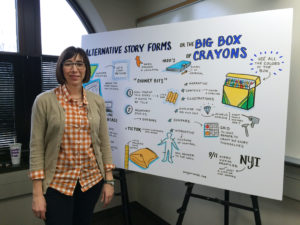

Graphic recorder Jo Byrne turned a half-hour lecture on the Big Box of Crayons into a lively visual summary. (Photo by Bella Grossi)

Journalism, done right, is storytelling. The upside to the increased demands on reporters — to be proficient in text and on video, with photos and maps and social media and on and on — is that journalists have more and more tools to tell stories well. In other words: a big box of crayons.

A few decades ago, a print reporter who wanted to tell a story probably stuck with text in a traditional story form. The story might be “arted up” with some photos. The newspaper design revolution of the ’80s made photography and informational graphics more integral. Seeking answers to declining circulation, newsrooms accepted a wider array of story forms, from lush narratives to “chunky bits” packages that broke stories into short pieces and parts. Good journalists realized that made storytelling richer. It was like moving from the 12-pack of crayons to the 24-crayon carton; you could draw with more shades of nuance. The internet and newsroom changes gave more journalists access to many more storytelling tools — 96, even 120 crayons.

That metaphor helped some anxious journalists in my old newsroom find hope amid the challenges of becoming digitally focused. But they were experienced storytellers who had lived through the last few decades of newsroom change. How could I communicate the same message to journalism students? Last semester, I found a great answer, through the talents of a graphic recorder named Johnine (Jo) Byrne.

To understand graphic recording, start with the idea of “sketchnoting” — supplementing, with small sketches, the notes you take while interviewing or listening to a lecture. You don’t have to be a trained artist. If you can draw stick figures, arrows and boxes, you can add sketches to notes. Graphic recorders such as Doug Neill say adding sketches as you take notes helps you remember more content.

Graphic recorders develop this skill to the point that visuals may dominate text — and they do it in public. Their work is not intended to be a complete summary, but rather highlights that will spur the memory. Watch a graphic recorder distilling a speech on the fly, and you can see metaphors become literal images. Watch one corral a community discussion onto poster board, filling it from edge to edge, and you can discover unnoticed connections. I wish I’d have thought, when I was an online editor, about getting a graphic recorder to work with us. Sketchnotes of political debates, perhaps?

Byrne’s work popped up in my Facebook feed while I was putting together the syllabus for a Writing Across Platforms course. I reached out, asking if she would speak to my class. She upped the ante by suggesting she graphically record me. In a meta lesson, I talked about the Big Box of Crayons and the imperative to use multiple tools to tell full stories, while Byrne demonstrated the concept by sketching my lecture.

After I was done — about a half hour — she spoke and took questions from students. Based on comments afterward, a lot of students got a clear understanding of what the Big Box of Crayons means. They learned other things, too. Several students later showed me how they’d started adding sketches to their class notes. I saw what studies say is true: With sketchnoting, students became more engaged and analytical during a lecture, and retained more information afterward.

Interested? Mike Rohde has written how-to books and has lots of links to related content on his site.

For teachers, the best way to explain this — whether you focus on taking better notes, or use it to help journalism students understand the storytelling potential of the Big Box of Crayons — is to get a graphic recorder into your classroom. Jo Byrne’s session in Writing Across Platforms got more student engagement than almost anything else; students buzzed about it long after she left.

There are many lessons you can — excuse the pun — draw from having a graphic recorder in your class. For example, I kept slipping and referring to Byrne as a graphic reporter, because I saw parallels between the way she boils down an event to memorable moments and the way news stories are exercises in selectivity.

In a later class, I talked about long-form journalism and the concept of planting “gold coins” to keep the reader interested. During my Big Box of Crayons lecture, I had briefly mentioned the bad old days when an editor measured our productivity by collecting the envelopes newsroom librarians used to store bylined stories. He’d take a ruler to each reporter’s clip envelope, literally measuring how stuffed it was. Byrne illustrated that anecdote — not, she explained, because it was important, but because it was a striking image that would spur other memories. That, I told my students, was one way of thinking about gold coins in writing: not necessarily packed with information, but interesting and intriguing.

If you want to bring someone like Byrne into your classroom, you’ll have to search. There are surprisingly few people who do this. Byrne is, as far as I can tell, the only graphic recorder based in Northeast Ohio. Still, there are enough people like her spread around the country that I would think most journalism schools had at least one graphic recorder nearby. In addition to “graphic recording,” I’ve seen this work referred to as “graphic facilitation” and “strategic illustration.”

Whatever you call it, watching someone transform a discussion into visual notes is a great way to get a group’s attention and open minds to the possibilities when storytelling moves beyond primary colors.

No Responses