20 Jul 2016

How to turn news into a story people will care about

In my journalism classes, I’ve ditched the standard lists of “news values” limited to a handful of items and used to vaguely suggest why certain stories are published and others aren’t. I explained my reasons in two previous posts (News values reconsidered and News judgment with the audience in control). I replaced them with a

19 Jul 2016

News judgment with the audience in control

In print newsrooms I’ve worked in, certain colleagues were acknowledged as having better or worse news judgment. The “news values” taught in journalism school weren’t referred to explicitly. News judgment was like charisma; you had it or you didn’t. In digital newsrooms, there is temptation to swing the other way, reducing story decisions to consultation

25 Jun 2016

News values reconsidered, or, why ‘man bites dog’ matters

How do journalists decide if a story is worth reporting? They consult the list of possible news values — easy-peasy, since everyone agrees there are just 10 … or 12 … or a different 12 … or eight … or nine-ish … or five … or seven … I confronted that confusion when I started

17 Jun 2016

Teacher’s guide: ‘Startup,’ the podcast

Two things I learned as a business journalist: One, business news can be deathly boring. Two, the best fix is to tell good stories. That’s why anyone teaching a class on entrepreneurialism would be smart to use the first season of “StartUp,” the podcast from Gimlet Media. Gimlet is the brainchild of Alex Blumberg, a

15 Jun 2016

The business of publishing, Part 2

This post is about how to pay for journalism. SPOILER ALERT: I do not solve the equation and save the business. While I was preparing to teach a course on the business of (journalism) publishing, smart people advised me to forget a textbook. Instead, they said, use the news. Riff off industry developments. I created

09 Jun 2016

The business of publishing: Lesson for a journalism teacher

Sure, I said, I can teach the Business of Publishing. Granted, all I remember learning about it in college was that libel is expensive, so it’s cheaper to be accurate. But I was a financial journalist for years. And, like every journalist of my generation, I got a crash course in the finances of journalism

08 Jun 2016

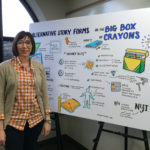

Sketchnoting & the big box of crayons: Lesson for a journalism teacher

Journalism, done right, is storytelling. The upside to the increased demands on reporters — to be proficient in text and on video, with photos and maps and social media and on and on — is that journalists have more and more tools to tell stories well. In other words: a big box of crayons. A

02 Jun 2016

Lesson for a journalism teacher: Meeting them where they are

The assignment for the students — in their first college journalism writing class — was the kind I remembered from my own student days. I gave them facts about a fire: who saw it first, where it happened, when, damages, etc. They had to write a first paragraph, a summary “lede.” The summary lede is

17 Dec 2015

Reporter gets rude emailer in trouble with boss, saves world

There are two ways to respond to crude insults. One way is to remain above them, either ignoring the jerk or responding politely. The other way is to embrace the insult as an excuse to behave like a jerk yourself. Guess which way a reporter for the Wall Street Journal took recently? The screenshot accompanying

02 Dec 2015

It can’t be said enough: Leave ‘said’ alone

Dear English teachers of North America: Stop it. Stop teaching the repetitive, boring five-paragraph essay. Stop telling yourself that you teach a writing class, not a grammar class. And to this list of sins a new one can be added, according to the Wall Street Journal: Stop telling your students to stop using “said.” “There