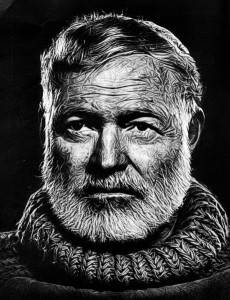

Hemingway the reporter vs. Hemingway the author

I was doing some research for a presentation on narrative journalism and journalistic fiction when I ran across a 2012 blog post by Bill Henderson on Write a Better Novel. He put side by side a passage from a story Ernest Hemingway filed for the Toronto Star and the same scene in his first fiction, “In Our Time.”

I was doing some research for a presentation on narrative journalism and journalistic fiction when I ran across a 2012 blog post by Bill Henderson on Write a Better Novel. He put side by side a passage from a story Ernest Hemingway filed for the Toronto Star and the same scene in his first fiction, “In Our Time.”

One thing I find interesting is that several other commentaries I found about journalists turned fictionalists insist that terse, blunt, spare sentences in fiction are an import from journalism, and they cite Hemingway as a chief example. It appears to me that Hemingway’s newspaper report has a somewhat more complex mix of sentences, more use of adjectives, even a simile slipped in.

One thing I do notice in both the article and the story — and something I’ve seen in the fiction of many former journalists — is The List. “Cows, bullocks and muddy-flanked water buffalo.” “A young pig, a scythe and a gun, with a chicken tied to his scythe.” There it is in the story, too: “mattresses, mirrors, sewing machines, bundles.” It strikes me that authors trained in creative writing are taught (at least in the workshop I’m participating in) to eliminate details that do not contribute to the theme, that don’t recur, that don’t carry meaning beyond their presence. Reporters, though, may tend to see themselves as objective cameras, recording everything and letting the reader sort it out. Or do we pile up these lists because they’re an easy way to describe a scene? Then, too, there’s the “empty your notebook” syndrome — I wrote it down, I have to use it.

My first time reading through these two passages, I thought the second was more personal, more of a close-up. Rereading them, though, they blend together, and I find the original report even more moving than the rewrite.

In the pre-electronic (and certainly pre-digital) era reporters strove to paint the picture rather than act as a camera lens. In doing so they brought us into the scene, made it come alive, gave us a sense of the emotions, without injecting a point of view. Today’s reporters, perhaps partially constrained by instant deadlines, strive for bare bones reporting that strips away the flesh of many stories. They seem to mistake sterility for objectivity and thus remove the main reason for turning to written reports — the joy of reading good writing.