100 books every journalist must read

New Kings of Non-Fiction, Ira Glass (ed.)

It feels a bit like swimming upstream to recommend so many books related to long-form journalism in the age of listicles and clickbait headlines. Maybe, though, that’s the point. Only by reminding yourself over and over of the power of the well-written word will you be able to resist the call to abandon it entirely. This collection curated by Ira Glass, founder and host of public radio’s “This American Life,” provides digestible chunks of work from a fair variety of authors.

Other voice: Whet Moser, Chicago Reader. “Overall, it’s a fine anthology, not a bad compromise as these things go. Literary Journalism, edited by Norman Sims and Mark Kramer, is better front-to-back but more conservative; John D’Agata’s The New American Essay is riskier but less reliable.”

If Colin Duffy and I were to get married, we would have matching superhero notebooks. We would wear shorts, big sneakers, and long, baggy T-shirts depicting famous athletes every single day, even in winter. We would sleep in our clothes. We would both be good at Nintendo Street Figheter II, but Colin would be better than me.

The Newspaper Designer’s Handbook, Tim Harrower & Julie Elman

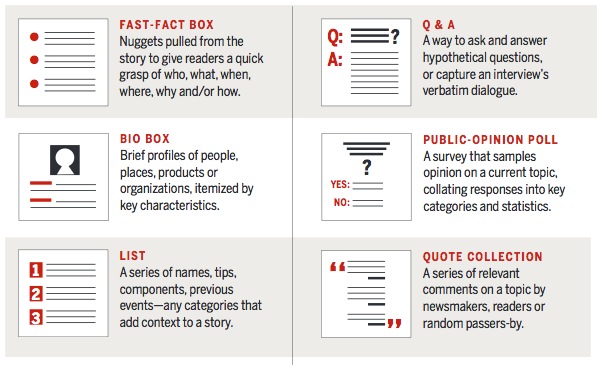

I designed my last print pages in the mid-1990s, and the books I relied on for my design guidance seem old-fashioned now. I remember — this was in the early ’80s, at the Detroit Free Press — suggesting to my boss that instead of starting each of the six to eight stories on our front page with a few inches of type, we create a centerpiece that was like a magazine cover, pushing the reader inside for the whole story. He just couldn’t see how it would work, and — I confess — I wasn’t sure what I meant, either. Better designers had similar ideas, and by the end of the ’90s circulation declines industrywide had worked the same magic that they used to work for individual papers: They made editors reckless, willing to entertain the notion that doing the same thing over and over might not work. Designers got to design. When I asked my design colleagues what book best speaks to today’s print design, they pointed me to Harrower. His book is a thorough look at the field — not just designing particular pages, but drilling down to details such as byline styles and nameplates. He and current co-author Julie Elman provide guidelines for photo editing and infographics and discuss “alternative story forms” — ways to tell a story that break away from the standard 12 inches of text and a cloud of dust. (The example below is from that section. Click it to go to the full PDF on Harrower’s site.) The writing is conversational and the book’s design itself is lush and inviting. Textbook note: In addition to the regular link for a new copy of the textbook, I’ve included a link for used (and possibly less expensive) copies.

Other voice: Steve Dorsey, Detroit Free Press. “The Newspaper Designer’s Handbook is not just the greatest single source for teaching and learning about publication design, but it continues to evolve with each edition, perfecting and adapting as the industry itself grows and evolves.”

Find in my store | Find on AbeBooks

Nickeled and Dimed, Barbara Ehrenreich

Ever since the journalism honorary fraternity Sigma Delta Chi made the horrible mistake of pretending its members were professionals — so, sometime in the ’20s — the American version of the craft became infested with stuffy, status quo-protecting notions about what our ethics should be. One particular irritant is the notion that journalists must always declare themselves as such in the midst of their reporting. Bull crap. In “Nickeled and Dimed,” Barbara Ehrenreich reports on what life is like for low-wage workers by the obvious but radical tactic of becoming one herself. Read this to understand why in-the-flesh reporting is important; to remind yourself to pay attention to the least of society; and to provide the comforting knowledge, when the job of reporting gets to you, that it could be much worse.

Other voice: Anne Colamosca, BusinessWeek. “Ehrenreich’s descent into this underclass life filled her with a burning anger. She rails against a universe in which workers are banned from talking to each other, denied trips to the bathroom, forced to allow management searches of their purses at any time, and kept on their feet–or their knees–for hours on end with few breaks.”

I feel oppressed, too, by the mandatory gentility of the Wal-Mart culture. This is ladies’ and we are all ‘ladies’ here, forbidden, by storewide rule, to raise our voices or cuss. Give me a few weeks of this and I’ll femme out entirely, my stride will be reduced to a mince, I’ll start tucking my head down to one side.

Nobody Asked Me, But …, Jimmy Cannon

The sports sections of newspapers were where creativity went to hide when it was banned from news columns as unrespectable. I’ve never been sure whether that was because top editors didn’t read the sports pages, or because that was the only coverage they read for personal pleasure rather than occupational obligation. In any event, Jimmy Cannon is a classic example of great talent hiding out in sports (although slipping in observations about everything else). The book’s title was the lead on those columns where he would punch out one-sentence thoughts on a wide array of topics, a device that has been borrowed by pretty much every columnist old enough to have read him.

Other voice: Dave Anderson, New York Times. “In modern sports writing, there have been two patron saints — Red Smith and Jimmy Cannon.”

The stooped old man spoke a private language of insult and a .38 bulged in his hip pocket. The voice was grouchy and harsh. If New York could talk, it would sound like Lou Stillman.

One More Time: The Best of Mike Royko, Mike Royko

I will accept no rebuttal: Mike Royko was the best columnist of the 20th century. He was like a symphony musician who could sit first chair with four different instruments: biting humor, bittersweet reminiscence, dogged reporting, sharp satire. If you have not read Royko, you have not seen the mountaintop. “One More Time,” published after his death, collects some of his classics. To a sizable portion of the metropolitan area, Royko simply was Chicago, a city that took a perverse pride in its corruption: Citizens reserved the right to complain, but balled their fists should anyone from outside dare to criticize.

Other voice: Jacob Weisberg, Slate. “Reading these gems in the new posthumous selection, One More Time: The Best of Mike Royko, I found myself wondering: Why doesn’t anyone write a newspaper column this good anymore? Royko wasn’t quite a Twain, or a Mencken, but his writing was distinctive and memorable and in its time the closest thing to lasting literature in a daily paper. Royko could make you laugh and make you think, stir outrage at a heartless bureaucrat, or bring a tear to the eye when he flashed a glimpse of the heart hidden beneath his hard shell.”

It was a big day for the punks. … They stood on the sidewalk and swore and spat and shouted at the civil rights people … When a blond kid spewed a mouthful of spit into the interior of a car, his friends pummeled his back as though he had struck a grand-slam home run. And the punk looked proud but humble.

Paris Was Yesterday, 1925-1939, Janet Flanner

A collection of items written for The New Yorker as letters from Paris. They are, as the years in the book’s title would indicate, about events rapidly fading into lost memories. For modern journalists, the value lies not only in Flanner’s powers of observation and skill as a writer, but most of all in her ability to pack short passages with information, wit and analysis. She puts immense faith in her readers to read into her items that which she hasn’t written. This is a lesson for every blogger.

Other voice: New York Times. “Proving the current state of under-disciplined journalism, Flanner could polish a multifaceted sentence to crystalline brilliance. Take this, from 1927 on the scandalous influence of Duncan the dancer: ‘The clergy, hearing of (though supposedly without ever seeing) her bare calf, denounced it as violently as if it had been golden.’ ”

Tristan Tzara, founder of the Dada movement, which most people seem to think has something to do with bad taste in modern pictures, has just married the daughter of a rich Swedish industrialist. … He and his wife, on what the French law now probably calls his money, are bulding a huge modernist house in Montmartre. Tzara is a great man of small stature and wears a monocle.

The Photographer’s Eye, John Szarkowski

I presume that anyone who has made it to a journalism school has, somewhere along the line, been exposed to classic works of English and American literature — and probably will be exposed to more through college classes. That’s one reason I winced at the editor whose first recommendations for reading were the Bible and Shakespeare. I agree that those who would use a mode of communication should be aware of what’s come before and how the field’s conventions evolved, however. And I don’t think most would-be journalists have gotten much exposure to the history of photography. I’ve chosen “The Photographer’s Eye” for that purpose — out of a large array of potential choices — because it is relatively concise, focuses more on concepts than chronology, and gives the readers only brief paragraphs of exposition before allowing them to look at photographs and draw their own conclusions. And, also, because: John Szarkowski.

Other voice: Sean O’Hagan, The Guardian, in a profile. “Szarkowski was a good photographer, a great critic and an extraordinary curator. One could argue that he was the single most important force in American post-war photography.”

The photographer learned in two ways: first, from a worker’s intimate understanding of his tools and materials (if his plate would not record the clouds, he could point his camera down and eliminate the sky); and second he learned from other photographs, which presented themselves in an unending stream.

Pictures on a Page, Harold Evans

My edition dates to 1987, and many of the photos in it are even more ancient. It’s still valuable because the principles Evans lays out are timeless. He combines practical visual advice with stern admonitions to avoid using photography to mislead.

Other voice: Rick Poynor, Designers & Books. “Evans analyzes a wealth of compelling news pictures and their presentation on the page, providing a masterly lesson in visual history as he guides and informs.”

The camera cannot lie; but it can be an accessory to untruth. Political enemies smile at each other for a hundredth of a second and the next day the newspaper reader absorbs the warmth of their friendship.

The Press, A.J. Liebling

A.J. Liebling wrote about newspapers for The New Yorker, and no one who’s come around since has been close to matching the intelligence and humor of his media criticism. Although the events he covers here are now far in our past, the issues remain startlingly relevant. Consider Liebling’s column on “The Great Gouamba.” Gouamba, he explains, is the word in some part of Africa for “the inordinate longing and craving of exhausted nature for meat.” He uses that as background for the way newspapers went mad about the threat of rising beef prices. Every time I see panicky stories about a 10-cent increase in prices at Starbucks or a threat to the orange crop, I think: “gouamba.”

Other voice: Jack Shafer, Slate. “Liebling invented, almost from scratch, the journalistic genre of literary press critic, but because he wrote as well as he did, he seems to have closed the door on the way out. Liebling’s literary vision is too vivid to imitate, and it’s hard to imagine someone trumping it.”

The end-of-a-newspaper story has become one of the commonplaces of our time, and schools of journalism are probably giving courses in how to write one: the gloom-fraught city room, the typewriters hopelessly tapping out stories for the last edition, the members of the staff cleaning out their desks and wondering where the hell they are going to go.

Prisoner without a Name, Cell without a Number, Jacobo Timerman

About the worst punishment a journalist in America gets for practicing journalism is a short stint in jail imposed by a judge trying to pull out the name of a source. Even that is exceedingly rare. For expressing an opinion? No legal penalty. For telling the truth? None. “Prisoner without a Name” will drive home how grateful you should be for that. Jacobo Timerman was grabbed by Argentinian authorities, thrown in jail, stripped of his property, thrown out of the country. This is a book about tyranny and oppression and the evil that lives in men, but it is also a book about courage and principles and the value of journalism.

Other voice: Anthony Lewis, New York Times. “The prisoner is blindfolded, seated in a chair, hands tied behind him. The electric shocks begin. No questions are put to him. But as he moans and jumps with the shocks, the unseen torturers speak insults. Then one shouts a single word, and others take it up: ‘Jew … Jew … Jew! … Jew!’ As they chant, they clap their hands and laugh.The victim: Was he some unlucky social outcast? No, he was Jacobo Timerman, editor and publisher of a leading Buenos Aires daily newspaper, La Opinion. And in a sense he was lucky. For, unlike 15,000 other Argentinians who were seized by the military over the last five years, he lived. Timerman lived. And he has used that grace to write an extraordinary book about his experience. It is the most gripping and the most important book I have read in a long time: gripping in its human stories, not only of brutality but of courage and love; important because it reminds us how, in our world, the most terrible fantasies may become fact.”

They uprooted our telephone lines, took possession of our automobile keys, handcuffed me from behind. They covered my head with a blanket, rode down with me to the basement, removed the blanket, and asked me to point out my automobile. They threw me to the floor in the back of the car, covered me with the blanket, stuck their feet on tope of me, and jammed into me what felt like the butt of a gun.

I’d add “The Paper: The Life and Death of the New York Herald Tribune,” by Richard Kluger. The Trib was the great newspaper of the mid-’60s, with an oversized impact on our notions of quality — and effective — journalism. Too bad the numbers didn’t add up.

Thanks for commenting, Ed. I do have Jim Bellows’ book on the list, which includes his take as editor of the Trib. And Stanley Walker’s City Editor.

Some good books here, but some glaring omissions that I didn’t immediately find: Hiroshima by John Hersey, The Face of War by Martha Gellhorn, A Bright, Shining Lie by Neil Sheehan. Something from Richard Harding Davis and Stephen Crane.

Good choices, Chris. I decided I covered Harding Davis with The First Casualty, and I think I remember him being in the Treasury of Great Reporting. I was a bit concerned about over-representing war reporting.

“Precision Journalism”, by Phil Meyer. This 1972 book launched the idea that reporters should use social science methods like polling and statistical analysis, and led to the widespread adoption today of data journalism in newsrooms around the world.

Thanks for the suggestion, Steve. I read that back in journalism school when I considered applying my computer science minor to a newsroom job. I went with the Data Journalism Handbook for the list, but you’re right, Meyer’s book launched the era of data journalism.

I agree about omitting Gellhorn.

Of your 100, only 18 are written or edited or about women. This seems unbalanced to me, given the preponderance of women in this industry, Nellie Bly onward. How about Marguerite Higgins?

Or the extraordinarily brave war reporter Marie Colvin or Janine Giovanni?

http://www.amazon.com/On-Front-Line-Collected-Journalism/dp/0007487967

I did the same count you did, Caitlin. It’s a concern. Some of the collections that are edited by men do, however, include women as contributors, so it’s not as lopsided as the count suggests. I considered adding a collection devoted solely to female journalists — the one already on my shelves is “Brilliant Bylines” by Barbara Belford, which includes short biographies. I wondered, though, if that might seem tokenism.

I would add my Ohio Wesleyan journalism professor’s book – Edwards, Verne. 1970. Journalism in a Free Society, Wm. C. Brown Co. Publishers.

I add the Journalist Code I once read – “If your Mother says she loves you, check it out.”

Thanks, Ann. That quote, by the way, comes from the (former) City News Bureau of Chicago (says this Chicago kid).

I’d certainly rethink In Cold Blood, given later information on how Capote cooked some of it. Ditto All the President’s Men, which played a little loose with narrative fact as a way to tee up the movie deal. And some of those j-school textbooks are by people who never wrote more than a memo or a term paper in their lives? No way do they belong. And lots of those books on this list are woefully out of date.

It Happened One Night, the Titanic book, deserves a mention. It was very early quality non-fiction narrative. And doesn’t anyone even remember Psmith: Journalist by Wodehouse, a classic in the genre?

James, I’m not sure who you’re referring to regarding the textbook authors. I explain my decisions regarding In Cold Blood and all the President’s Men in the list: Knowing those books, it seems to me, is essential to understand their impact on the craft.

I would add:

“Smiling Through the Apocalypse: Esquire’s History of the Sixties” – collects much of Esquire’s landmark journalism from that decade by Gay Talese, Norman Mailer, Tom Wolfe and others.

“America: What Went Wrong?” by Donald L. Bartlett and James B. Steele – the only book I can think of that became an issue in a presidential campaign, in 1992, over its analysis of how the American middle class was losing out. (The same authors revisited that theme a couple of years ago in “The Betrayal of the American Dream.”)

“The Selling of the President 1968” by Joe McGinniss – the first book to look behind how candidates are packaged and marketed, as they’ve been ever since.

“What Liberal Media?” by Eric Alterman – the first book that really pushed back against the conservative meme that “the media are all liberals.”

Anything by Roger Angell, whose New Yorker reporting on baseball is unparalleled.

Michael, thanks for commenting. Esquire writers are already well represented on the list — not counting Mailer, who’s not one of my favorites. I admire Bartlett and Steele, but I couldn’t find a place for them on the list; worth thinking about again.

I’d have to add William Shirer’s Berlin Diary. He was in the belly of the beast, reporting on Hitler’s rise to power — he even accompanied the Wehrmacht on their drive into France — and then he joined Murrow in the early days of radio news. And his Rise and Fall of the Third Reich showed that some journalists do recognize the need to go back and do a much deeper version of their initial reporting.

Hmm. I recently reread Shirer’s Rise and Fall and was put off by his homophobia.

Give Berlin Diary a try. It’s “pre-history” in that while we know what all of this means and how it will turn out, Shirer doesn’t, so you get a great sense of how difficult it was for journalists on the scene and everyone else to understand where Hitler was headed.

What’s missing from Berlin Diary are the actual stories Shirer wrote. He’s there at all of the major Nazi rallies, at every step in Hitler’s rise to power, he repeatedly describes the look on Hitler’s face as he is standing a few yards away, but he has to deal with Goebbels and the censors, so while we read what he is thinking, we don’t know what he is telling his readers. He’s aware that Jews are in trouble and trying to get out of Europe, but you don’t know if he ever wrote about, e.g. He eventually leaves, a year before Pearl Harbor, in part because he realizes he can’t tell his readers what is happening (and in part because he fears the Germans are about to arrest him as a spy).

Thanks for a heroic achievement in concocting this list. I haven’t had the time to truly digest, analyze, contemplate specific trade-offs, etc., but off the top here are some things I would have considered.

Edmund Wilson, “The American Earthquake.” Remarkable reporting and writing about the 1920s and 30s Saturation reporting and New Journalism decades before they came into fashion.

“Speaking of Journalism,” ed. William Zinsser. Corby Kummer’s relatively brief piece “Editors and Writers” is one of the single best things I’ve ever read on the craft of editing, a much tougher topic to talk about than how to write well.

Norman Mailer, “Miami and the Siege of Chicago.” You don’t like Mailer? Tough. Too influential and important to ignore. This is his best non-fiction.

Joan Diddion, “We Tell Ourselves Stories in Order to Live.” (anthology)

Nan Robertson, “The Girls in the Balcony.” History of discrimination against women at the NYT.

Kenneth Tynan, “Profiles.” Master of the form.

Jack Newfield, “The Education of Jack Newfield”

“The New Journalism,” ed. Tom Wolfe; “The Literary Journalists,” ed. Norman Sims. Two fine anthologies. Repeats stuff on your list but worth owning.

“The Reporter as Artist: A Look at the New Journalism Controversy,” ed. Ronald Weber. Fantastic overview, valuable not only for examples of personal journalism but for discussions, critiques, interviews and dissents.

John Reed, “10 Days that Shook the World.” Classic all the way around.

Seymour Krim, “Missing a Beat.,” ed. Mark Cohen. A highly influential and original voice growing out of the beat generation who was already forgotten by his death in 1989. This is a recent anthology but I’d encourage folks to scour used book stores for Krim’s own collections like “Views of a Nearsighted Cannoneer,” “Shake it For the World, Smartass,” etc.

Ralph Ellison, “Shadow and Act.” OK – Ellison’s essays aren’t conventional reporting, but no book will teach you more about the American experience, culture and race and therefore no book is more important for those who need to understand American culture, which is to say journalists.

Roger Angell, “Game Time.” An A+ anthology by the best baseball writer ever. Period. Full Stop. (Coda: Tom Boswell of the Washington Post is equally great on baseball and golf and it’s worth looking for his collections “How Life Imitates the World Series,” “Strokes of Genius” and “Why Time Begins on Opening Day.”

Solid choices, Mark. Thanks.

The “old editor” was right when he recommended the Bible and Shakespeare. Whether you’re an atheist or devout believer, every journalist should be up to speed on the literary and cultural allusions that have come into the language from the Bible: 40 days and 40 nights, manna from heaven, etc. Same goes for Shakespeare. And I would add Greek and Roman mythology. Too many journalists seem clueless at basic references.

In terms of books, I’ve recommended to many young (and not so young) journalists William Manchester’s “The Glory and the Dream,” a political AND cultural history of the United States covering the 1920s to early ’70s. I don’t know about anybody else’s high school education, but too often history classes ran out of time as they approached the World Wars and shortchanged all but the most basic stuff. The result: a relative “black hole” of knowledge on anything from that period on until the person was old enough to follow “current events.”

Don, I agree that journalists should have a basic cultural awareness. I don’t agree that such requires reading the Bible and Shakespeare. Knowing chapter and verse for manna from heaven won’t improve anyone’s writing or reporting. But I might even go along with the suggestion — if older journalists would agree that they must keep up to date with youth culture as well. For every young reporter who doesn’t know enough about post-War history, I can match you with older journalists who are still peppering their copy with allusions drawn from movies, songs, TV shows and books that are unknown to readers under 35.

An excellent suggestion, John. As an older journalist (23 years in the biz), I still try to read at least two books on the bestsellers list, see most of the major blockbuster films in the theater and listen to the songs that go viral. As for TV, I can’t stomach the reality shows, but the rest I watch on Netflix/Hulu/Amazon/YouTube/iTunes. Now I just need to find a way to become immortal, so I can find the time do even more.

Before you say, oh, Jesus, who let Hunter S. Thompson in the room, please consider Fear and Loathing in America: The Brutal Odyssey of an Outlaw Journalist / Gonzo Letters Volume II 1968-1976. These are the personal correspondences of a journalist at the height of his craft, committed to his craft at all costs, battling for truth and expenses.

Ed, I let Hunter in the room with “Fear and Loathing on the Campaign Trail,” already. The Gonzo Letters are interesting, though.

Love your list. I am not a journalist, only a reader who is fascinated by reporting, a gift from my parents who let me listen to Morrow when I was but a boy and got me hooked on new for life. Thanks for including Mencken, introduced to me by my uncle, a journalist, whose collection of Mencken I have in addition to my own copies. And thanks for Liebling, whose Earl of Louisiana was my young introduction to my own home state and city, and whose writing showed me what great expository, lively prose was all about.

So glad you included Edna Buchanan, Mike Royko, Studs Terkel and Ernie Pyle. These were the people I idolized when I first entered the field. Others I would recommend:

“Front Row at the White House: My Life And Times” by Helen Thomas

“Life on the Death Beat: A Handbook for Obituary Writers” by Alana Baranick, Jim Sheeler and Stephen Miller

“Thank You, Mr. President: A White House Notebook” by A. Merriman Smith

“City Room” by Arthur Gelb

“Late Edition: A Love Story” by Bob Greene

“Deadline” by James Reston

and

“My First Year as a Journalist: Real-World Stories from America’s Newspaper and Magazine Journalists” by Dianne Selditch

Thanks for the suggestions, Jade. And on behalf of my former colleague at The Plain Dealer, Alana Baranick, special thanks for mentioning Life on the Death Beat.

Alana is amazing, and her co-authors are award-winners as well (Jim even won the Pulitzer). If any young journalist wants to learn how to become an obit writer, this is the book to read first.

Disappointing that Dick McCord’s The Chain Gang didn’t make the list. A great read into Gannett’s shady history of crushing independents.

I’d never heard of McCord’s book before, Patrick. Which is a surprise, because my mom grew up in Peshtigo, north of Green Bay, and I spent a lot of summers up there so I’m somewhat familiar with the saga of the Green Bay papers. I’ll give it a look. Thanks!

No love for Charles Kuralt? It was Kuralt, not Woodward or Bernstein, who made me want to become a journo.

Thanks for the comment, Sam. I’m a print guy, myself, and had to fight that bias in assembling the list. Also had some concern about tilting the broadcast focus too much toward CBS, same reason I bypassed Cronkite’s autobiography. But worth a second thought.

As soon as you listed an SND annual, I gave up on this list.

The SND annual is the museum of modern journalistic decay. Your description of the “evolution” of design is laughable. What actually happened: A bunch of people who couldn’t hack it as editors came up with a way to redefine the work and to make editing of lower priority.

The result: A 40-year con game in which papers continue to claim they “attract” readers with their design, even though all circulation and sales numbers indicate otherwise. Some might call this “lying.”

The credibility of your list dropped to zero with that inclusion. I’m sure many pseudojournalists and others trying to cling to a level of self-importance will ruminate deeply about this list, but I’ve seen what I need to see.

In addition:

“Of your 100, only 18 are written or edited or about women. This seems unbalanced to me …”

Quotas as a guideline for quality — mmmkay. Someone must not have read much Ray Bradbury.

The call for quotas — another example of the total failings of modern journalism.

Hi, Bob! I feel honored to get my very own Robert Knilands trolling comment. This blog has made the big time, apparently. (For those of you who don’t know, Mr. Knilands is a frequent sniper on Internet forums about journalism, particularly about design.)

That’s a pretty weak counterargument. I had expected better, but I guess anyone who includes an SND annual in a list of must-reads has some issues.

Back to the oh-so-horrible-omissions, aka any book a self-important journalist DEMANDS inclusion for: I actually fished Roger Angell’s “Late Innings” out of the pile just a couple of weeks ago. There was time only to flip through a few random pages, but I remember it being an above-average read years ago. The big disappointment today was seeing the “circle the wagons” mentality that plagues far too much of what passes for sportswriting today. Nevertheless, I plan to get the book out again in the future, as I fully expect it will be several levels above the sewage that flows through today’s “sports” sections, many of which have sold out to weak social commentary and lame comedy routines.

Also, the page designers who are blissfully ignorant about yellow journalism and what it entailed should read:

“Emery, Edwin. The Press and America (Englewood Cliffs, N.J.: Prentice-Hall, Inc.), 1962.”

Stunning omission: ‘Byline: Ernest Hemingway’ – any journalist who wants to learn how to tell great stories can learn something here.

Bob, comments like yours are a good reason for lists like this — I’m finding out about great reads I haven’t seen on any similar lists. Thanks!

Homicide by David Simon is vital. So is The Word by Rene Capon–it is the single best book for a fledgling journalist–or any writer–to read. And Fear and Loathing in Las Vegas is overrated from a journalistic perspective. Fear and Loathing on the Campaign Trail is much better. McGovern’s campaign manager called it the least factual and most accurate depiction of the campaign for good reason.

I’ve heard a lot of support for Homicide. I’d never heard of Capon’s book. Regarding Fear and Loathing — I take your point, and comparing Boys on the Bus with Fear and Loathing on the Campaign Trail would be interesting. Thanks for your suggestions, Bruce.

How many of the books on this list are still in publication? I was searching for books on Nellie Bly a few years ago, and I never saw that one. I’m interested in picking up some of these.

Christie

All the books that have a “Find in my store” link underneath are available as new copies (or Kindle copies) from Amazon. For other books, the “Find on Biblio.com” or “Find on AbeBooks” links to send you to search results on those used-book sites. Using any of those links will earn me a small commission on books you purchase, helping cover the costs of assembling this list.

Indispensible Enemies by Walter Karp

Karp was Lewis Laphams right hand guy at Harpers.

Bill Moyers said he was one of the six greats whom

Molly Ivins would have joined by now.

Karp divides the world of politics into hacks and reformers

and shows the hacks of both parties colluding to keep

all reformers out of power. Karp also shows us the role

of dummy candidates and thrown elections.

Nothing in American politics makes sense before Karp

Everything in American politics makes sense

after you’ve read Karp.

Also Gothic Politics in the Deep South by Robert Sherrill.

Sherrill was an emeritus editor at the Nation and Ivins mentor

at Texas Monthly.

And George Seldes. And Molly Ivins.

Thank you all for your suggestions, which i will

print out and read.

How about Night of the Gun by David Carr?

Wonderful list. Thank you for sharing the wealth. I’m not a journalist (I used to teach English Lit and currently run workshops on Innovation) but I’m fanatical about journalism. I particularly loved William E. Blundell’s “The Art and Craft of Feature Writing: Based on The Wall Street Journal Guide”. It’s a wee bit stodgy but it nails the vital importance of a clear underlying structure.